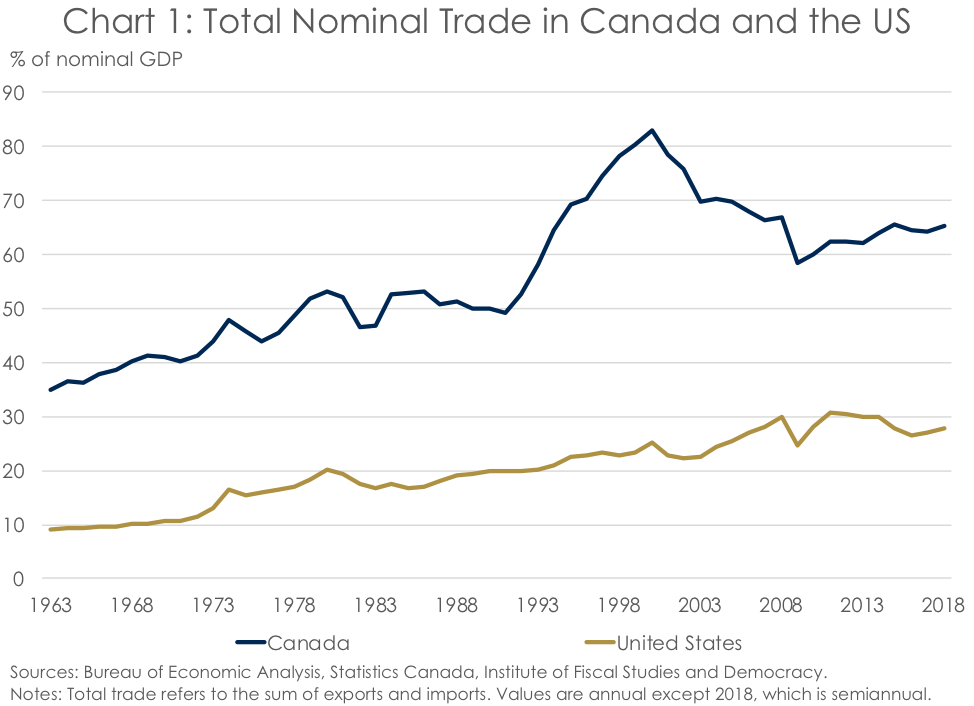

by Randall Bartlett

The reality show which is U.S. trade policy continues to lurch forward, with each episode seemingly ending in a “To be continued …” as opposed to a season finale. The Trump administration remains hellbent on raising the cost of imports for American consumers and businesses by slapping tariffs on a hodgepodge of goods from abroad. Canada has been drawn into the fray as a consequence, reluctantly putting retaliatory tariffs on imports from the US in July following the introduction of levies on steel and aluminum headed to the Good Ole US of A.

But since the tariff tit-for-tat this past summer, negotiations between these traditional trading partners have broken down, with the US inking a deal with Mexico and leaving Canada out in the cold. North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) renegotiations have resumed in earnest since, but Canada has played coy, first unwilling to back down in its religious devotion to supply management, and more recently around Canadian cultural industries and the Chapter 19 dispute resolution mechanism.

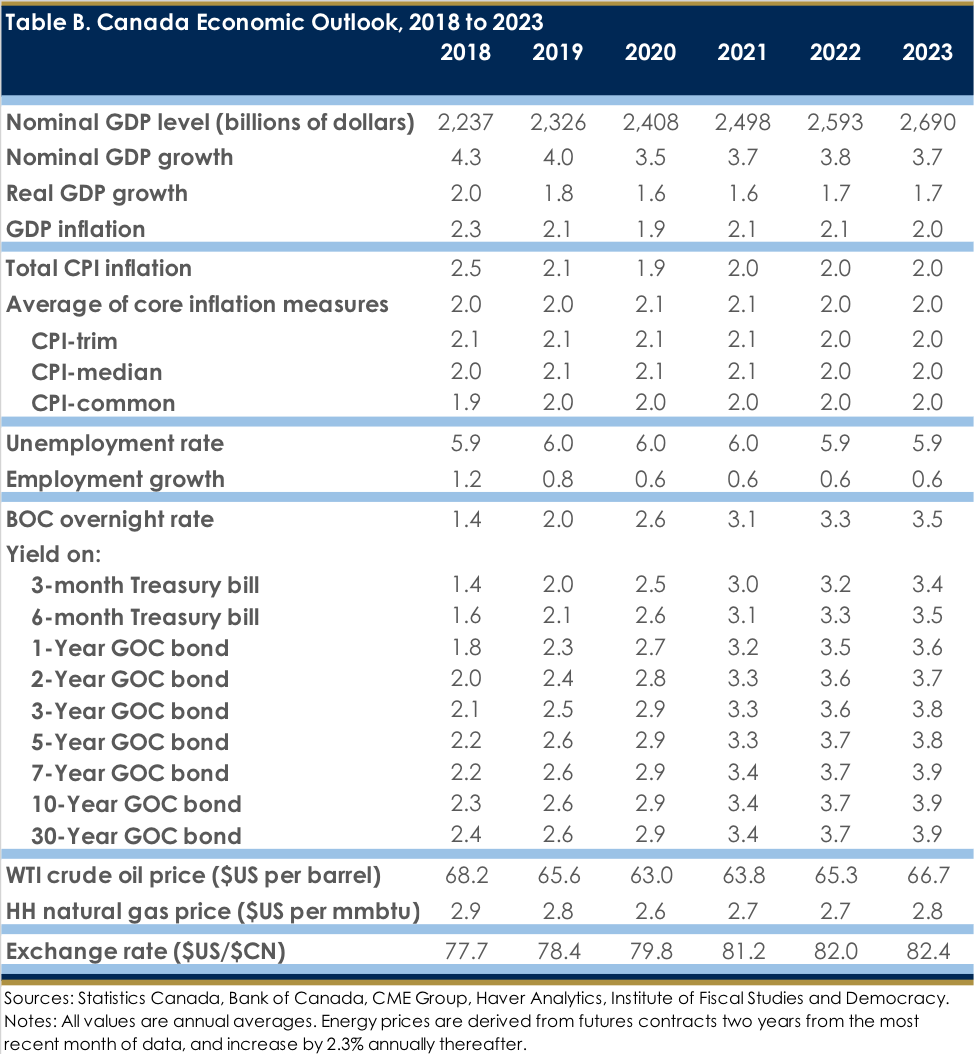

Much ink has been spilled in attempting to estimate the impact of the measures north of the 49th, most recently by the Bank of Canada. And it’s for good reason. Canada is a trading nation, with the share of total trade (exports plus imports) dwarfing that of the US when measured as a share of their respective economies (Chart 1). The threat of auto tariffs also continues to loom large if a deal isn’t reached – a risk that has become even more acute with the renewed escalation of reciprocal tariffs being levied by the US and China.

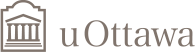

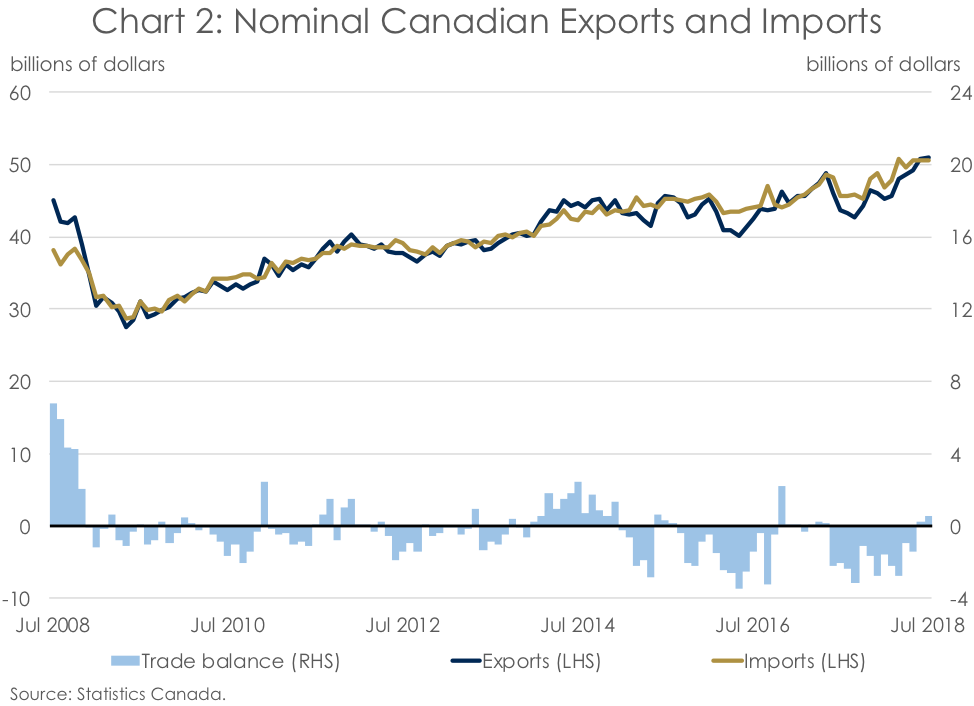

But recent trade data have been notably more positive than some analysts had anticipated. June 2018 trade data came in very positive, with exports outpacing imports by a wide margin. And while July data was more mixed, nominal exports reached their highest level since monthly trade data began being compiled. This helped to push the Canadian trade balance into surplus for the second consecutive month (Chart 2). Of course, the story is wildly different when drilling down into the steel and aluminum numbers, but the drag in these areas was modest when compared to the boon elsewhere.

And who do Canadians have to thank for this robust trade growth? Well, the US economy, of all things. Despite President Trump’s best efforts, the surging U.S. economy is supporting solid global trade, and particularly with America’s number one trading partner. At the heart of the recovery have been U.S. consumers, finally bringing their pent-up demand to the fore, supported by near-record-low unemployment rates and gradually accelerating wage growth (Chart 3). But businesses have also played their part, supported by better global sales and a tax regime at home that was made more internationally competitive at the start of the year (Chart 4). Stronger domestic demand has pushed imports higher, leading to expectations that trade will drag on U.S. real GDP growth in the third quarter. Indeed, the U.S. economy has shown such consistent strength that the U.S. Federal Reserve has hiked rates three times in the last year and further hikes are anticipated on the horizon as monetary policy returns to normal.

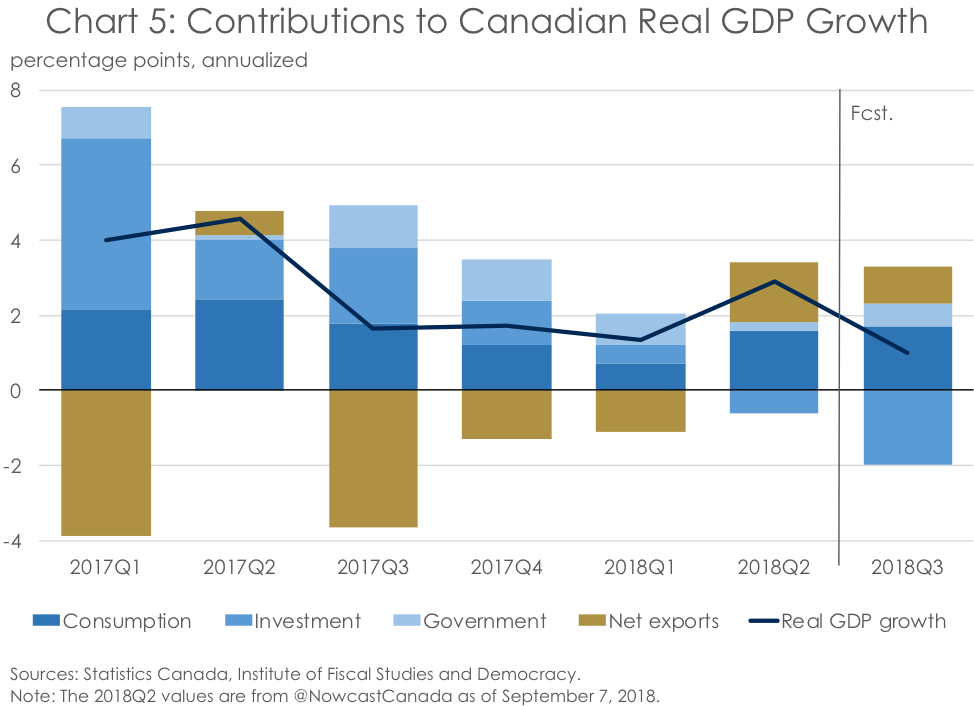

This strength stateside has bolstered growth in the Great White North, with trade doing some of the heavy lifting in early 2018. In the second quarter of 2018, net exports regained much of the ground lost in the prior two quarters, and trade data from July 2018 suggest that this momentum has persisted into the third quarter (Chart 5). In contrast, business investment has pulled back from its surging performance in 2017, calling into question to view of some commentators (notably the Bank of Canada) that a virtuous cycle of export demand and business investment may have begun.

But the Canadian economy is doing well enough that the need for higher interest rates is difficult to deny. According to the Bank of Canada, Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO), and Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy (IFSD), the output gap – the percent difference between real and potential GDP – is near or in positive territory, meaning the economy is operating at or above its trend (Chart 6). This view has been supported by gradual upward grind in wage growth and underlying price inflation, in part as a result of an unemployment rate that continues to hover around historic lows (Chart 7). Notably, the recent surge in July 2018 headline CPI inflation to 3.0% year-over-year was largely a function of higher fuel prices, which the Bank said it looked through when it made its rate decision in September. And while the Bank of Canada has rightly increased its focus on the impacts of rising interest rates on highly-indebted households, Canadian consumers appear to have largely shrugged off the higher cost of borrowing.

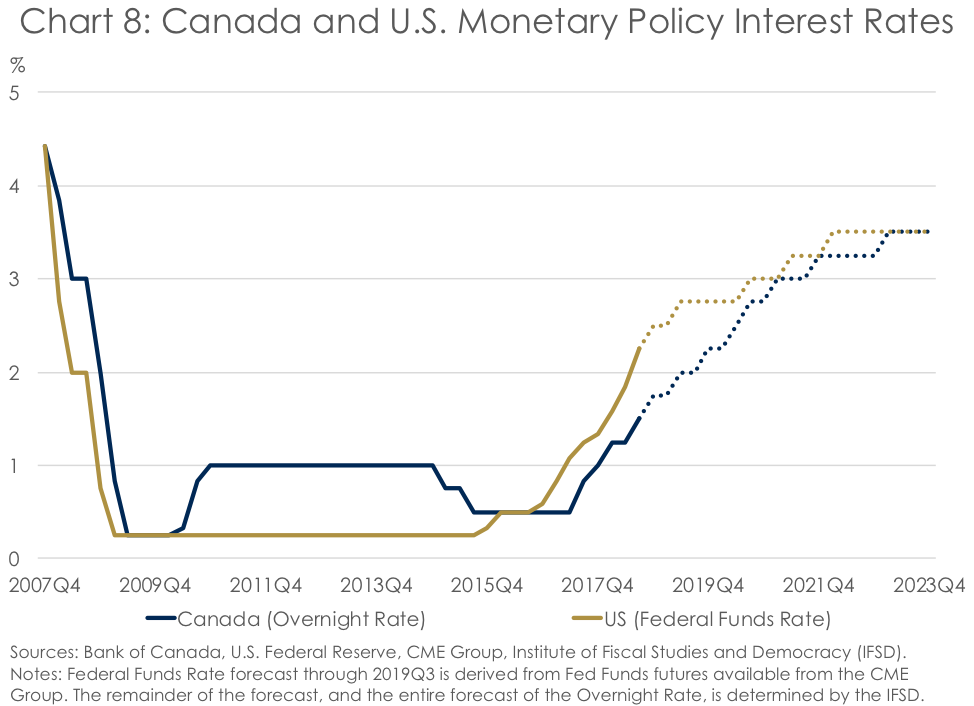

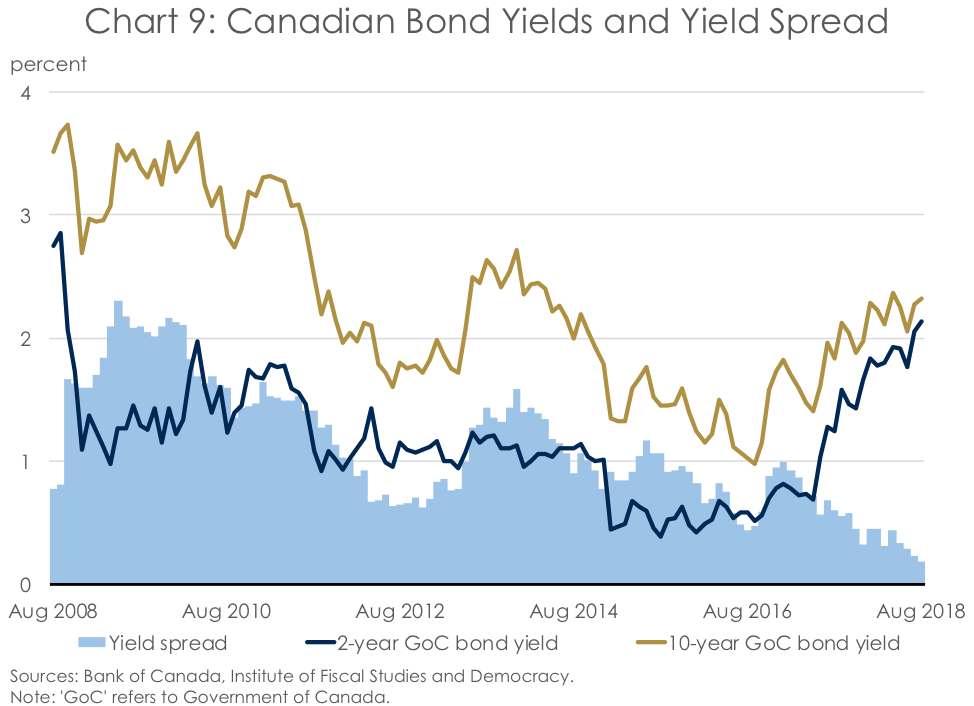

Taking all of this together, it’s a safe bet that interest rates are going to move higher in Canada, with the Bank of Canada’s next move likely to come in October 2018 (Chart 8). This has raised some concern that short-term interest rates will continue to rise faster than those at the long-end of the yield curve (Chart 9). The spectre of yield curve inversion – the level of short-term interest rates rising above long-term rates – has reared its ugly head as a result. And given an inverted yield curve is an oft-cited recession indicator, a not insignificant group of analysts on both sides of the 49th have cringed at the thought of further monetary policy tightening.

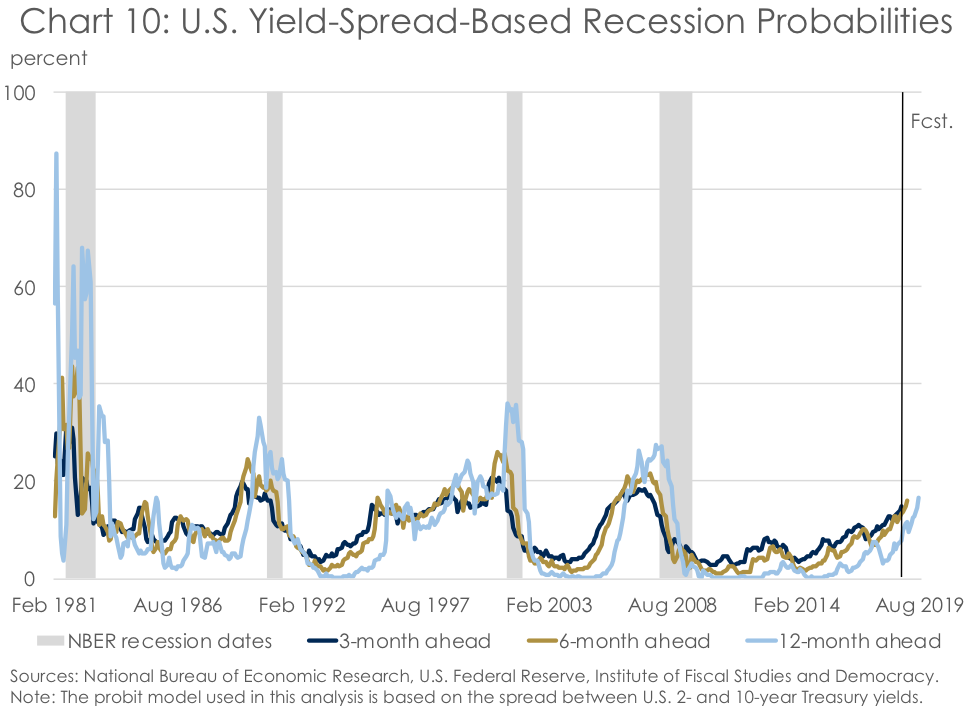

However, the IFSD doesn’t believe that an inverted yield curve occurring in the next couple of years, in Canada or the US, is the most likely scenario. According to our models, the yield curve will flatten considerably over the next couple of years as monetary policy interest rates begin to close in on the neutral rate – the central bank rate consistent with an economy operating at its potential and inflation that has returned to target. But the glacial pace of interest rate hikes by the Bank of Canada, and to a lesser extent the U.S. Federal Reserve, suggest that these central banks won’t be overly heavy-handed when it comes to rate hikes. Indeed, a basic probit model based on the spread between yields on 10-year and 2-year U.S. Treasury bonds constructed by the IFSD supports this view, with the probabilities of a recession in the coming 3, 6, and 12 months at 15%, 16%, and 17%, respectively (Chart 10). But, crucially, while these probabilities remain low, they are rising and approaching levels where some caution is warranted. Of possible more concern is that President Trump has started to express his dissatisfaction with the Fed’s actions. While remote, the possibility of a threat to the independence of the most important central bank in the world is worrisome.

But rising interest rates are really just one potential area where a policy mistake could derail the current bumper economic expansion in North America. Trade is, of course, the big question mark. While tariffs on steel and aluminum have proven insufficient to set the Canadian economy back, at least in the short term, the continued threat of levies on exports of automobiles and auto parts looms large. Negotiations around NAFTA, on the other hand, remain an ongoing moving target, with aspirations of a deal ebbing and flowing with every tweet and off-the-cuff comment. But, as Bank of Canada Governor Stephen Poloz has noted, the risks around higher tariffs are difficult to include in a forecast until measures are actually enacted.

Conclusion

Since the last IFSD Canadian Economic Forecast was published in June 2018, the risks to the outlook remain broadly unchanged albeit slightly more elevated. Protectionist trade policies south of the border, and the bluster surrounding them, remain an omnipresent risk. Recently, this risk has been accompanied by concerns around a further flatting, and possible inversion, of the yield curve. But, while spreads between short- and long-term interest rates have continued to narrow recently, the risks of an inverted yield curve and the potential for a recession seem somewhat overblown. And while the current outsized pace of economic growth isn’t likely to last, as central banks raise interest rates to cool economies that are operating at or above their potential, it will take a significant policy error to derail the expansion. If this happens, we’ll no doubt have the Trump administration to thank as opposed to technocrats at central banks.