by Helaina Gaspard

Moments of major change can set a country, a policy issue or an organization on a new course. But how do you get there? Can you force that change or is there a magical alignment of interests and forces required for a critical juncture? Not all change has to come from major shocks, sometimes change can be gradual and build up over time, creating important – albeit gradual – shifts in course and outcomes. Major change however, tends to come from a major shock.

It took the death of baby Jordan Rivers Anderson in hospital to ensure First Nations children were not caught in a jurisdictional battle between the provincial and federal governments when it comes to their health care. Jordan’s Principle now requires that First Nations children in need of medical care get the health services immediately, leaving the battle over who pays between orders of government for later. The child’s tragic death became a critical juncture that forced a change in the way First Nations children access government services.

In case of First Nations child and family services, the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal (CHRT) 2016 ruled that Canada discriminated against First Nations children by not ensuring the equitable provision of welfare services on reserve as exist elsewhere in the country. The CHRT demanded that the government reform the system. The ruling was clear and significant and created the opportunity for change.

From an institutionalist’s perspective, reforming the system means altering the incentives and rules by which it is governed. Simply closing the funding gap in the current system that’s not working is not a solution by itself. More is required. A renewed system that drives better results for children and addresses funding inequities should be the goal. (Full disclosure: we at the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy at the University of Ottawa were asked by the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) and the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society to work with agencies to inform a response to the CHRT on the current costs and future needs of agencies providing child and family services (CFS). Visit our project website for more information).

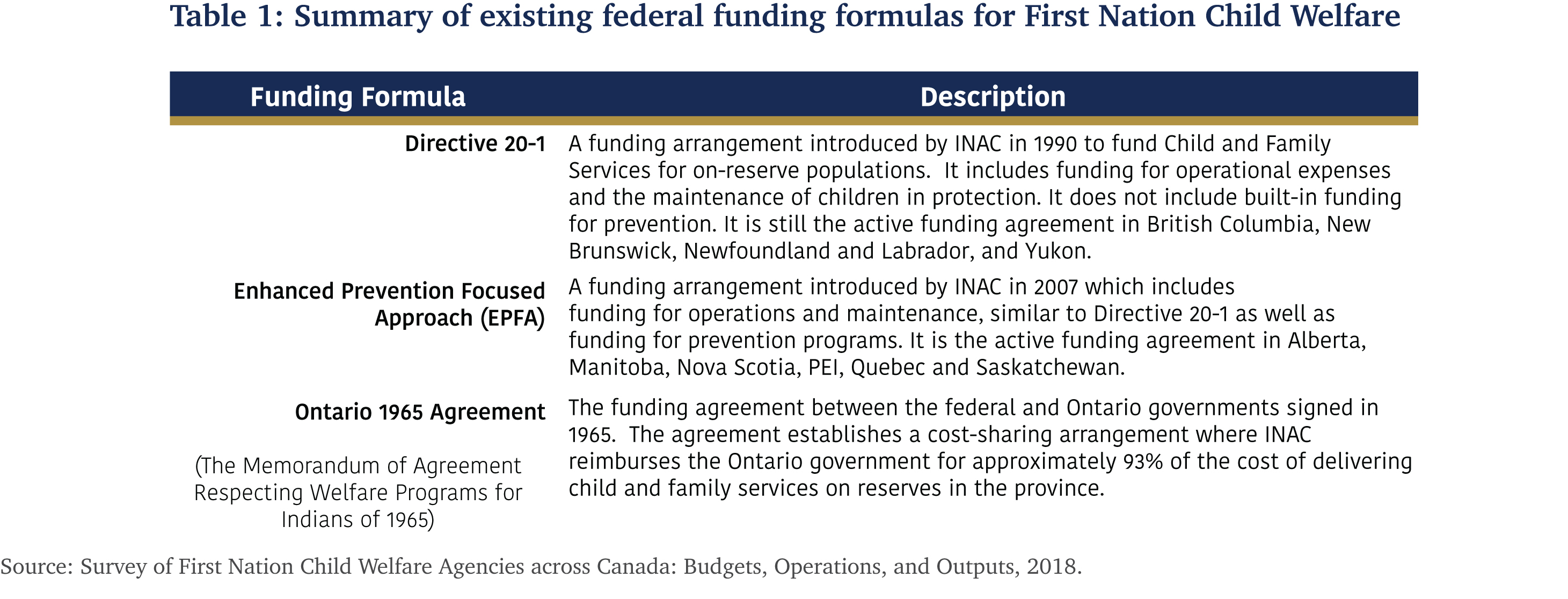

As it stands, First Nations CFS agencies are being funded to typically provide protection and prevention services to their on-reserve communities through one of three funding formulas (see Table 1). However, the flow and timing of that funding can be inconsistent and often does not align to mandates. These existing formulas generally require that children enter into care in order to unlock funding.

These arrangements (according to available program data), costed roughly $768,037,213 in 2016-17. This funding for the First Nations Child and Family Services program would have been allocated to fund agencies and their services. Budget 2018 added further commitments of 1.4 billion dollars (focused on prevention, over five years) for CFS.

The money alone doesn’t tell the full story.

With many agencies working to keep children with their families and in their communities, the result has been agencies finding creative ways to get their work done in spite of the current formulas’ rules and incentives. There are examples of agencies across Canada who have succeeded in promoting family integration, and even in reducing the rates of children in care, by finding ways of navigating the multi-tiered funding structure. Intensive family preservation programs, the removal of parents program and agency-commissioned university degree programs for social workers in First Nations CFS are only a few examples of how agencies have been innovating to support their children, families, and communities. Agencies should be succeeding due to their good work in fostering family and child well-being in community, not because they have figured out a way around the existing funding structure.

So, how do we get to a new architecture for First Nations CFS?

The current federal government has demonstrated an openness to change when it comes to First Nations child and family well-being. Announcements in Budget 2018 that focused on health, early childhood learning, and related areas like clean water and housing are directional consistent with a new approach to CFS. The major challenge however, remains defining and implementing a funding approach that incentivizes better outcomes for children in consultation with agencies and communities.

Consultations by IFSD with 64% of all 104 First Nations CFS agencies across Canada helped to define crucial directions for a future CFS program architecture. The main purpose of a new program might be fostering the holistic well-being of children and families in their communities. The new program, based on consultations with agencies should be guided by two important elements:

- Self-determination: Agencies should have decision-making authority to allocate and spend their funding as they determine to be most appropriate to meet the needs of their communities. Informed by First Nations laws and culture, the governance of CFS should be the purview of the agencies who are accountable for delivering protection and prevention services to their communities.

- Recognition of differences: Agencies come in different sizes, with different mandates, capacities, and experiences. New funding architectures should meet agencies where they are now and support them as they meet their future goals. There is no single approach that can best support agencies (no cookie cutter approach).

Transforming the new vision into a program architecture requires consideration of funding, performance measurement, and outcomes. Funding should be allocated in blocks in the areas of protection, prevention, maintenance, capital, operating, data & governance, enabling agencies to spend based on the particular needs of their community. Rather than having constraints imposed by other orders of government on how and when an agency can spend, the approach to funding should be in blocks where agencies are accountable for managing their resources through a grant-style allocation. The new spending rules would alter incentives. Instead of working around the system, agencies could focus on working with the system to plan and deliver their services with regularized funding allocations that align to their operations.

Anytime public money is being transferred to another order of government or organization, there is an expectation, in statute, policy or guideline, for reporting on spending and on results. When you measure the right things, you can obtain information to improve operations and planning in the short-, medium-, and long-terms. Reporting on the wrong indicators merely becomes an overhead burden, as it does not link inputs, outputs and outcomes to the attributes of high performance. Financial and performance reporting in a new program architecture should align to key activity and spending areas, i.e. protection, prevention, maintenance, capital, operating, data & governance. This means focusing on the inputs (resources human and financial) to deliver services, the outputs (the products or uptake of these services), and the outcomes (the results in the community, related to overall well-being).

Outcomes, especially in social areas like CFS can be difficult to assess. However, there are outcomes in education, health, and family well-being that can be useful proxies in understanding changes in a community. The goals of a new program should emphasize holistic well-being of children and families in their communities. This means focusing on equitable outcomes rather than equality between First Nations populations on-reserve and other individuals off-reserve. Programs like that of the Martin Family Initiative (MFI) that promote child and maternal well-being through community-led programming can encourage sustained advancement. MFI has local mothers supporting and sharing-knowledge with each other as learning centres are built for early childhood education. Defining program goals in the context of the population being served would be an important indicator of whether or not broader results in education, health, and family well-being are being achieved.

Canada has an opportunity for major change in First Nations child welfare with the CHRT’s ruling. The current government is on a tight timeline both with respect to the Tribunal’s jurisdiction and the election cycle. To make good on its promises for better results for First Nations children and their families, it should work with agencies and learn from their experiences and those of their communities to realign rules and incentives to set a new direction for CFS. A critical juncture is an opportunity to chart a new course forward. Will Canada seize the opportunity? These moments don’t come around very often. It’s now the time to start rowing together in the same direction.