Author: Valere Gaspard, Ph.D. (cand.), uOttawa, Research Fellow, Western University Leadership and Democracy Lab

Executive Summary

The link between Arctic sovereignty and the well-being of Inuit is rooted in dual duties of the Canadian state: (1) broad duties to all Canadians in its territory and (2) specific duties to Inuit through treaty obligations. Accomplishing these dual duties legitimizes the political authority of the Canadian state in the Arctic, especially since Inuit are the region’s majority population.

This research note substantiates the linkage between Arctic sovereignty and the well-being of Inuit. In addition to demonstrating the linkage between sovereignty and the well-being of Inuit, this research note also explains why this connection matters.

If the Canadian state cannot fulfill these duties as sovereign (specifically, to the majority population in its Arctic territory), then its claim to those territories weakens or fail at both the domestic and international level. This consequently weakens its capabilities to defend and secure its Arctic region.

To substantiate these claims, this research note uses evidence about (1) Canada’s Arctic and population, (2) Inuit Constitutional Rights and Treaty Agreements, and (3) Canada’s political interest in the Arctic (Section I: Background information) to develop a framework linking Arctic sovereignty and the well-being of Inuit (Section II: Framework: Arctic Sovereignty and the well-being of Inuit).

I. Background information

The three sub-sections in Section I of this note inform the proposed framework on Arctic sovereignty and the well-being of Inuit in Section II.

i. Canada’s Arctic Region (Inuit Nunangat) and its population

Canada’s Circumpolar Regions account for 40% of Canada’s territory and approximately 70% of its coastline.[1] For the purposes of this research note, Canada’s Arctic region[2] is considered the regions Inuit term “Inuit Nunangat”, which includes the northern area of the Northwest Territories and part of northern Yukon (the Inuvialuit Settlement Region), Nunavut, Nunavik in Northern Quebec, and Nunatsiavut in Northern Labrador (see Figure 2 in the Appendix).[3] Inuit Tapiritt Kanatami (ITK), the national organization representing Inuit in Canada, states that there are 51 communities across the Inuit Nunangat.[4] Statistics Canada estimates that out of the 70,545 Inuit living in Canada, approximately 69% live in Inuit Nunangat. Table 1 demonstrates that Inuit are the majority population in each of the Inuit Nunangat’s four regions.

Table 1: Population breakdown across Inuit Nunangat

| Region | Inuit population | Total population | Percentage of Inuit out of total population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inuvialuit region[5] | 3,145 | 5,310 | 59.2% |

| Nunavut[6] | 30,860 | 36,600 | 84.3% |

| Nunavik[7] | 12,595 | 13,990 | 90% |

| Nunatsiavut[8] | 2,090 | 2,320 | 90.1% |

| Inuit Nunangat (four regions combined) | 48,690 | 58,220 | 83.6% |

The percentage of Inuit relative to the total population of Inuit Nunangat highlights an important consideration in the discussion on Arctic sovereignty. Not only do 69% of Inuit in Canada live in the Arctic, but most of the individuals in Canada’s Arctic are Inuit. Consequently, any circumstances or decisions that specifically impact Inuit also influence the majority population (and largest group) that reside in Canada’s Arctic territory.

ii. Inuit Constitutional Rights and Treaty Agreements

Inuit are recognized under Canada’s Constitution Act, 1982 (s. 35) as aboriginal peoples and therefore have recognized and affirmed treaty and aboriginal rights.[9] This means that in addition to any broad normative obligations the Canadian state has towards its residents and/or citizens (i.e., protection and well-being), it also has specific obligations to Inuit regarding treaties and rights.

Canada’s Crown currently has five agreements with Inuit Treaty Organizations in the following regions: (1) the Inuvialuit Final Agreement (for the Inuvialuit Settlement Region);[10] (2) the Nunavut Agreement (for Nunavut);[11] (3) the Nunavik Inuit Land Claims Agreement[12] as well as (4) the James Bay and Northern Québec Agreement[13] (for Nunavik); and (5) the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreements (for Nunatsiavut).[14] Table 2 lists key principles from these treaty agreements.

Table 2: Examples from Inuit treaty agreements

| Treaty agreement | Examples of key principles |

|---|---|

| Inuvialuit Final Agreement | 1) Helping to preserve Inuvialuit cultural identity and values within a changing northern society (s. 1(a)). 2) Enabling Inuvialuit to be equal and meaningful participants in the northern and national economy and society (s. 1(b)). 3) Protecting and preserving the Arctic wildlife, environment and biological productivity (s. 1(c)). 4) Ceding aboriginal claims, rights titles and interests to the region(s) within the sovereignty or jurisdiction of Canada, subject to the rights and benefits in the agreement (s. 3) – however, this does not annul aboriginal rights guaranteed under the Constitution Act, 1982 or other rights given to Canadian citizens. |

| Nunavut Agreement | 1) Clarify and provide rights (e.g., ownership and use of lands, decision-making concerning wildlife harvesting, conservation of land, water and resources, including the offshore, of land to ownership, use of lands, etc.) (Preamble). 2) Provide Inuit with financial compensation and means of participating in economic opportunities (Preamble). 3) Encourage self-reliance and the cultural and social well-being of Inuit (Preamble). 4) Ceding aboriginal claims, rights titles and interests to the region(s) and water(s) within the sovereignty or jurisdiction of Canada (s. 2.7.1) – however, this does not annul aboriginal rights guaranteed under the Constitution Act, 1982 or other rights given to Canadian citizens. |

| Nunavik Inuit Land Claims Agreement | 1) Provide certainty regarding rights to ownership and use of lands and resources, including marine resources (Preamble). 2) Nothing in the Agreement shall deny that Nunavik Inuit are an aboriginal people of Canada (includes maintaining rights to participate in and benefit from government programs for Nunavik Inuit or aboriginal people, and any rights or benefits under the James Bay and Northern Québec Agreement) (s. 2.3). |

| James Bay and Northern Québec Agreement | 1) “In consideration of the rights and benefits herein set forth in favour of the James Bay Crees and the Inuit of Québec, the James Bay Crees and the Inuit of Québec hereby cede, release, surrender and convey all their Native claims, rights, titles and interests, whatever they may be, in and to land in the Territory and in Québec, and Québec and Canada accept such surrender. (s. 2.1.) 2) In response, Canada undertakes obligations to give, grant, recognize and provide rights, privileges and benefits outlined in the agreement to the Inuit of Québec. |

| Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreements | 1) “The Agreement sets out principles for the establishment of a free and democratic government for Inuit” (Preamble). 2) Nothing in the agreement denies that Inuit are aboriginal people of Canada or “Inuit are “Indians” within the meaning of section 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867” (s. 2.3.1), and does not impact their ability to participate in or benefit from programs for aboriginal people (s. 2.6.1). 3) “Inuit hereby cede and release to Canada and the Province all the aboriginal rights which Inuit ever had, now have, or may in future claim to have within Canada” (s. 2.11.2) |

In essence, the treaties create an agreement akin to a social contract between the Canadian state and each of the Inuit Treaty Organizations. According to social contract theorists, citizens trade-off part of their natural freedoms to the state and sovereign, and in return receive benefits from the state such as protection of life, property, or social services.[15]

In the case of Inuit, the listed treaty agreements cede certain claims and titles to the group’s traditional territory (while maintaining their rights as Aboriginal people), and in return are guaranteed protected rights by the Canadian state. While these treaties recognize the sovereignty of the Canadian state within the Inuit Nunangat regions, Inuit recognition of Canadian sovereignty is premised on receiving the rights and benefits that are guaranteed in the agreements.

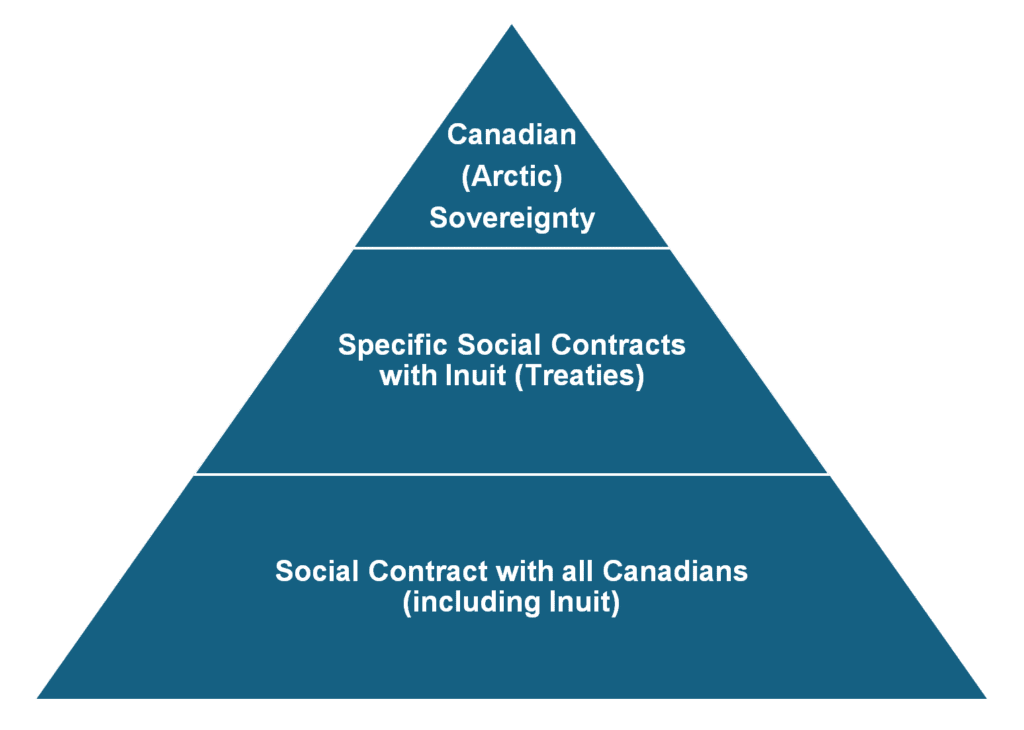

Ultimately, these treaty agreements highlight that the sovereignty of the Canadian state in its Arctic is rooted in two separate levels of social contracts:

This is an important assumption for the framework on Arctic sovereignty and the well-being of Inuit in Section II of this research note, since it substantiates that the Canadian state, as sovereign, holds two-levels of social contract obligations to Inuit (one that applies to all individuals in Canada, and one that applies specifically to Inuit).

In addition to these social contract obligations pertaining to Inuit well-being, it is important to recognize the harms of the Canadian state’s colonialism on Inuit[16] and the impacts it has on their current well-being. While obligations pertaining to reconciliation fall outside the scope of this research note, they remain an important consideration in the broader topic of Inuit well-being.

iii. Canada’s political interest in the Arctic

Political interest in Canada’s Arctic is not new. Canada began taking substantial actions to assert and enforce its sovereignty in the 20th century.[17] More recently, the federal government released its Arctic and Northern Policy Framework (September 2019),[18] Arctic Foreign Policy (December 2024),[19] and has made promises (March 2025) to expand the Northern and Arctic operations of the Canadian Armed Forces so that it “will be better placed to defend Canada’s Arctic presence and sovereignty”.[20]

In 2019, Canada’s Arctic and Northern Policy Framework listed “clear priorities and actions set out by the federal government and its partners”[21] such as nurturing families and communities, creating jobs, growing Arctic and northern economies, investing in energy, transportation and communication infrastructure, advancing reconciliation, and ensuring Canada’s northern and Arctic residents are safe, secure and well-defended. While Canada’s 2024 Arctic Foreign Policy references the 2019 framework in its Executive Summary,[22] the 2024 document describes the Arctic as “a theatre of interest for many non-Arctic states and actors aspiring for a greater role in Arctic affairs”[23] and advances four policy pillars to “support a stable, prosperous and secure Arctic”: (1) “Asserting Canada’s sovereignty”, (2) “Advancing Canada’s interests through pragmatic diplomacy”, (3) “Leadership on Arctic governance and multilateral challenges”, and (4) “Adopting a more inclusive approach to Arctic diplomacy”.[24] Consequently, the policy pillars infer that Canada’s contemporary priorities in the Arctic pertain to defence, Canada as an actor on the international stage, and preparing for an Arctic Ocean that “will become an increasingly viable shipping route between Europe and Asia during the summer”.[25]

Given the current emphasis on Arctic sovereignty in Canada’s contemporary political context, it is important to examine the linkage between Arctic sovereignty and the well-being of Inuit.

Canada proposes in its Arctic Foreign Policy that “national security is also supported by human security” and that “resilient local communities are vital to national defence”.[26] Inuit make up 83.6% of the Arctic’s total population and are the majority in these local communities. Therefore, to uphold the Arctic Foreign Policy’s goals of sovereignty through resilient local communities and human security, Canada must support the well-being of Inuit.

However, there is no definition of well-being for Inuit or for living in Inuit Nunangat. While Inuit Treaty Organizations or other actors may espouse their own visions, there are no publicly documented measures of progress toward defined goals.

Inuit should therefore define their vision of well-being and provide goals for the Canadian government to meet in partnership with Inuit.[27] Meeting these well-being goals (and regularly measuring their progress) reinforces and legitimizes the Canadian state’s claim to Arctic sovereignty through the presence of Inuit and resilient communities in Inuit Nunangat.

II. Framework: Arctic Sovereignty and the well-being of Inuit

“Sovereignty can be broadly and provisionally understood as a legitimated claim to political authority.”[28]

The connection between Canada’s Arctic sovereignty and the well-being of Inuit has been suggested before. Three examples include: (1) Mary Simon’s proposal (as President of Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK)) that for “Canada to assert its sovereignty legitimately in the Arctic, it must also ensure that Inuit are treated as all other Canadians are … with the same standard of education, health care, and infrastructure that is the foundation of healthy communities across Canada”;[29] (2) the Inuit Circumpolar Council’s Declaration on Sovereignty in the Arctic which declares that the “foundation, projection and enjoyment of Arctic sovereignty and sovereign rights [for Arctic states] all require healthy and sustainable communities in the Arctic”;[30] and (3) ITK’s statement that “prospering Inuit communities are integral to Canada’s sovereignty and long-term security and defence objectives in the Arctic”.[31]

The three examples connecting Canada’s Arctic sovereignty and the well-being of Inuit consider sovereignty through the lens of what Loukacheva calls a ‘Northern vision of sovereignty’, which assumes a state’s legitimate claim to political authority (sovereignty) is shown through building “civil society, social well-being, economic self-reliance, and participation of citizens in decision-making processes affecting the Arctic”.[32]

In classic ‘social contract theory’ (the theory that rationalizes the creation of the state), the state is sovereign when citizens enter a compact with it. Citizens forfeit part of their natural freedoms (i.e., operating and living free from state coercion) to the sovereign/state and in return receive benefits and protections. These include protection from violence[33] or protection of property[34] among other examples. As the legitimate political authority, the state (which derives its authority through its citizens) has obligations to those citizens through its social contract. If the state does not fulfill its social contract, then the basis for the existence of that state (what gives it sovereignty and legitimate authority) is no longer there.[35] For this reason, “sovereignty can be broadly and provisionally understood as a legitimated claim to political authority”.[36] This infers that a key component of a state’s legitimacy is the “population’s sense of obligation or willingness to accept [the state’s] authority”.[37]

The rationale of connecting well-being to sovereignty is therefore plausible through both the lens of a ‘Northern vision of sovereignty’ as well as classic understandings of social contract theory. The state achieves sovereignty through the social contract with its citizens, and then reinforces its legitimate claim to political authority (its sovereignty) through a variety of tactics, including the well-being of the residents/citizens in its territory.

This rationale on sovereignty and legitimacy, combined with the evidence from Section I of this research note provides a clear response to the question: “does Arctic sovereignty require the well-being of Inuit?” Specifically, the well-being of Inuit is required for the Canadian state to demonstrate its Arctic sovereignty both domestically and internationally:

i. Demonstrating Canadian Arctic sovereignty domestically

The social contract between citizens and the state makes the state sovereign. The state has a duty through its social contract to all citizens/residents in its territory. However, as shown in Section 1, the Canadian state also has specific social contracts (treaties) with Inuit, on top of its regular duties towards citizens/residents in its jurisdiction. Therefore, Inuit recognition of the state’s sovereignty is two-fold: (1) the fulfillment of the social contract that applies to all citizens and (2) the fulfillment of the social contract (treaties) that only apply to Inuit (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Inuit’s social contracts with the Canadian state

Since Inuit are the majority population in the Arctic, their recognition of the legitimacy of the Canadian state and its sovereignty is crucial for claims of Arctic sovereignty. To receive ongoing recognition from its Arctic population, the Canadian state must fulfill its social contracts – ensuring the broader well-being of Canadians and the more specific well-being of Inuit.

In turn, their presence and well-being in the Arctic (as Inuit living in Canada) reenforces Canada’s claims of Arctic sovereignty.

ii. Demonstrating Canadian Arctic sovereignty internationally

In addition to fulfilling the Canadian state’s social contracts with Inuit, ensuring the well-being of Inuit is also vital for Canada to receive recognition of Arctic sovereignty from the international community. Some argue that receiving recognition at the international level is an essential part of demonstrating sovereignty.[38] In the past, the Canadian state has attempted to demonstrate its sovereignty over its Arctic territory (land, ice, and waterways) through ‘symbolic sovereignty’ which “consists of actions taken to fulfill the format requirements of sovereignty under international law”.[39] A historic example of this was opening a RCMP detachment on Ellesmere Island at the Bache Peninsula (despite there being no human residents on the island at the time) in 1926. In more recent decades, the Canadian state has practiced ‘developmental sovereignty’ (what international law considers the “consolidation of sovereignty”) which consists of formulating “a policy for the development of territory under its control”.[40] In the late 20th century, the Canadian state used the administration of law in criminal cases to demonstrate its “effective administration of territory” in the Arctic.[41]

For the 21st century, the Canadian state can demonstrate its ‘effective administration of territory’ through Inuit well-being. This would be in line with the Canadian government’s political priorities, as stated in Section 1 of this research note. The Canadian government’s Canada’s Arctic and Northern Policy Framework (2019) lists priorities related to Inuit well-being (nurturing families, creating jobs, etc.) while its Arctic Foreign Policy (2024) states that it will assert Canada’s sovereignty in the Arctic to “support a stable, prosperous and secure Arctic”. These priorities are not mutually exclusive.

Part of demonstrating sovereignty at the international level consists of developing territory under the state’s control – therefore, partnering with Inuit (the majority population in the Arctic territory) to create infrastructure and policies that result in their well-being is necessary for exercising sovereignty in the Arctic. If the Canadian state only exercises its sovereignty through presence (such as expanding the Northern and Arctic operations of the Canadian Armed Forces) it risks only fulfilling the criteria of symbolic sovereignty over the Arctic. To fully demonstrate its Arctic sovereignty, it must work with Inuit to help ensure their well-being (the majority population of Canada’s Arctic).

If Inuit well-being and access to services (such as education and healthcare) do not meet the same standards as other Canadians, then it is more difficult for the Canadian state to demonstrate its legitimacy and sovereignty over the Arctic.

If the Canadian state is sovereign over its Arctic, it must guarantee the well-being of the citizens/residents that live there, like it would for Canadians living in other parts of its territory. If the Canadian state cannot fulfill its social contracts with the people of the Arctic, its claim to those territories weakens or fail both domestically and internationally.

III. Appendix

Figure 2: Map of Inuit Nunangat

[1] Government of Canada. Canada and the Circumpolar Regions. (Ottawa: Government of Canada, 2025). https://www.international.gc.ca/world-monde/international_relations-relations_internationales/arctic-arctique/index.aspx?lang=eng.

[2] The definition of what constitutes Canada’s Arctic region can vary. Inuit Tapiritt Kanatami considers it the Inuit Nunangat region. Other accounts limit the region to the Arctic Circle (the northern area of Canada’s three territories), the North Circumpolar Region (including the entirety of Yukon and the Northwest Territories (in addition to Inuit Nunangat) but excluding Northern Labrador), or Northern Canada (Canada’s Arctic terrain) as a whole (Canada’s three territories, Northern Manitoba, Northern Quebec, and Northern Labrador).

[3] Inuit Tapiritt Kanatami (ITK). An Inuit Vision for Arctic Sovereignty, Security and Defence. (Ottawa: ITK, 2025), 5.

[4] ibid.

[5] Statistics Canada. Indigenous Population Profile (Inuvialuit region), 2021 Census of Population. (Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 2023). https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/ipp-ppa/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&SearchText=Inuvialuit%20region&DGUID=2021C1005086&GENDER=1&AGE=1&HP=0&HH=0

[6] Statistics Canada. Indigenous Population Profile (Nunavut), 2021 Census of Population. (Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 2023). https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/ipp-ppa/details/page.cfm?Lang=e&SearchText=Nunavut&DGUID=2021C1005085&GENDER=1&AGE=1&HP=0&HH=0

[7] Statistics Canada. Indigenous Population Profile (Nunavik), 2021 Census of Population. (Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 2023). https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/ipp-ppa/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&DGUID=2021C1005084&SearchText=nunavik&HP=0&HH=0&GENDER=1&AGE=1&RESIDENCE=1

[8] Statistics Canada. Indigenous Population Profile (Nunatsiavut), 2021 Census of Population. (Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 2023). https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/ipp-ppa/details/page.cfm?Lang=e&SearchText=Nunatsiavut&DGUID=2021C1005083&GENDER=1&AGE=1&HP=0&HH=0

[9] Government of Canada. Consolidation of Constitution Acts, 1867 to 1982. (Ottawa: Government of Canada, 2025). https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/const/const_index.html

[10] Indian and Northern Affairs Canada. The Inuvialuit Final Agreement as amended: consolidated version. (Ottawa: Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, 2013 (2005)). https://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/9.853161/publication.html

[11] Indian and Norther Affairs Canada. Agreement between the Inuit of the Nunavut Settlement Area and Her Majesty the Queen in right of Canada. (Ottawa: Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, 2013 (1993)). https://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/9.696303/publication.html

[12] Government of Canada. Nunavik Inuit Land Claims Agreement. (Ottawa: Government of Canada, 2011 (2006)). https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1320425236476/1551119558759

[13] Ministère de l’Emploi et de la Solidarité sociale. Consolidated Agreement. (Quebec: Ministère de l’Emploi et de la Solidarité sociale, 1975). https://www.publicationsduquebec.gouv.qc.ca/produits-en-ligne/conventions/lois/james-bay-and-northern-quebec-agreement-and-complementary-agreements/consolidated-agreement/

[14] Government of Canada. Land Claims Agreement Between the Inuit of Labrador and Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Newfoundland and Labrador and Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada. (Ottawa: Government of Canada, 2010). https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1293647179208/1542904949105

[15] Thomas Hobbes. “Leviathan”;John Lockes. “Second Treatise of Government”; and Jean Jacques Rousseau. “On the Social Contract” in Classics of Moral and Political Theory: Fifth Edition, ed. Michael L. Morgan (Indianapolis/Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company, 2011).

[16] Mark B. Salter journal article “Arctic Security, Territory, Population: Canadian Sovereignty and the International” in International Political Sociology 13 (2019), notes on page 371 that Inuit have called the Canadian government into account for colonial acts including: the residential school system, relocation, the slaughter of sled dogs, and other policies.

[17] William R. Morrison. “Canadian Sovereignty and the Inuit of the Central and Eastern Arctic”, Inuit Studies 10, no. 1/2 (1986): 245. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42869548.

[18] Government of Canada. Canada’s Arctic and Northern Policy Framework. (Ottawa: Government of Canada, 2019). https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1560523306861/1560523330587

[19] Government of Canada. Canada’s Arctic Foreign Policy. (Ottawa: Global Affairs Canada, 2024). https://www.international.gc.ca/gac-amc/assets/pdfs/publications/arctic-arctique/arctic-policy-politique-en.pdf

[20] Prime Minister of Canada. Prime Minister Carney strengthens Canada’s security and sovereignty. (Iqaluit: Office of the Prime Minister, 2025). https://www.pm.gc.ca/en/news/news-releases/2025/03/18/prime-minister-carney-strengthens-canada-security-and-sovereignty

[21] Government of Canada. Canada’s Arctic and Northern Policy Framework. (Ottawa: Government of Canada, 2019), 2. https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1560523306861/1560523330587

[22] Government of Canada. Canada’s Arctic Foreign Policy. (Ottawa: Global Affairs Canada, 2024), 5. https://www.international.gc.ca/gac-amc/assets/pdfs/publications/arctic-arctique/arctic-policy-politique-en.pdf

[23] ibid.

[24] ibid, 16.

[25] ibid, 5.

[26] ibid, 17.

[27] These goals could entail requisite funding of programs, services, and infrastructure to support thriving Inuit communities in their unique contexts.

[28] Luke Glanville. “Sovereignty” in The Oxford Handbook of the Responsibility to Protect, eds Alex J. Bellamy and Tim Dunne (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016): 153. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198753841.001.0001

[29] Mary Simon. “Inuit and the Canadian Arctic: Sovereignty Begins at Home,” Journal of Canadian Studies 43, no. 2 (2009): 251. https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/50/article/384819/pdf

[30] Inuit Circumpolar Council. A Circumpolar Inuit Declaration on Sovereignty in the Arctic. (Greenland, Canada, Alaska, Chukotka: Inuit Circumpolar Council, 2009).

[31] Inuit Tapiritt Kanatami (ITK). An Inuit Vision for Arctic Sovereignty, Security and Defence. (Ottawa: ITK, 2025), 3.

[32] Natalia Loukacheva. “Nunavut and Canadian Arctic Sovereignty,” Journal of Canadian Studies 43, no. 2 (2009): 97. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/384826

[33] Thomas Hobbes. “Leviathan”in Classics of Moral and Political Theory: Fifth Edition, ed. Michael L. Morgan (Indianapolis/Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company, 2011), 635-39.

[34] John Lockes. “Second Treatise of Government” in Classics of Moral and Political Theory: Fifth Edition, ed. Michael L. Morgan (Indianapolis/Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company, 2011), 712-13.

[35] Jean Jacques Rousseau. “On the Social Contract” in Classics of Moral and Political Theory: Fifth Edition, ed. Michael L. Morgan (Indianapolis/Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company, 2011), 887.

[36] Luke Glanville. “Sovereignty” in The Oxford Handbook of the Responsibility to Protect, eds Alex J. Bellamy and Tim Dunne (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016): 153. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198753841.001.0001

[37] Thomas Risse and Eric Stollenwerk. “Legitimacy in Areas of Limited Statehood,” Annual Review of Political Science 21, (2018): 404.

[38] Stephen D. Krasner. “Abiding Sovereignty,” International Political Science Review 22, no. 3 (2001). https://www.jstor.org/stable/1601484

[39] William R. Morrison. “Canadian Sovereignty and the Inuit of the Central and Eastern Arctic”, Inuit Studies 10, no. 1/2 (1986): 246. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42869548.

[40] ibid, 247.

[41] ibid, 248.

[42] Inuit Tapiritt Kanatami (ITK). An Inuit Vision for Arctic Sovereignty, Security and Defence. (Ottawa: ITK, 2025), 5.