by Taylor Rubens-Augustson

(The IFSD has published a report on Early Childhood Development among First Nations: The Case for Early Intervention expanding on the below. You can find it here.)

Improving Canada’s relationship with Indigenous peoples was and continues to be a core component of the Liberal Party’s platform. Since coming into power, financial contributions for Indigenous issues would suggest they are committed to fulfilling this promise. Budget 2019 showed no signs of slowing down, with $4.5-billion dedicated to advancing reconciliation.[1] This is in addition to nearly $17 billion the federal government has already committed in the previous three 3 budgets.[2]

Although budgetary allocations are a good indication that Indigenous issues remain high on the government’s priority list, it is equally important to examine the actual outcomes these expenditures produce. Unfortunately, the most current statistics related to indicators of well-being among Indigenous peoples display stagnancy or only slight improvements that certainly have not come fast enough.[3]

There is no easy fix to such complex issues. However, there are certain programs that show promise for making a real difference over the long-term. Early intervention, which includes programs that aim to foster healthy early childhood development (ECD) in the youngest years of life (including during gestation), has emerged as an globally recognized approach to improving outcomes across the life course, especially among disadvantaged children in difficult family situations.[4] This is based on an abundance of research outlining how experiences in the earliest years of life – during the most rapid period of development – can influence an entire life trajectory.[5]

Approaches to early intervention vary based on community need, context and resources. Two of the most common include home visiting, whereby professionals or trained paraprofessionals support and educate parents in their child’s development, and early childhood education (or preschool), which often focuses on enhancing cognitive and non-cognitive abilities to improve readiness for entry into the formal school system.[6] Many interventions combine these two approaches in some capacity, and both aim to enrich a child’s environment in the early years.

(Please click to enlarge)

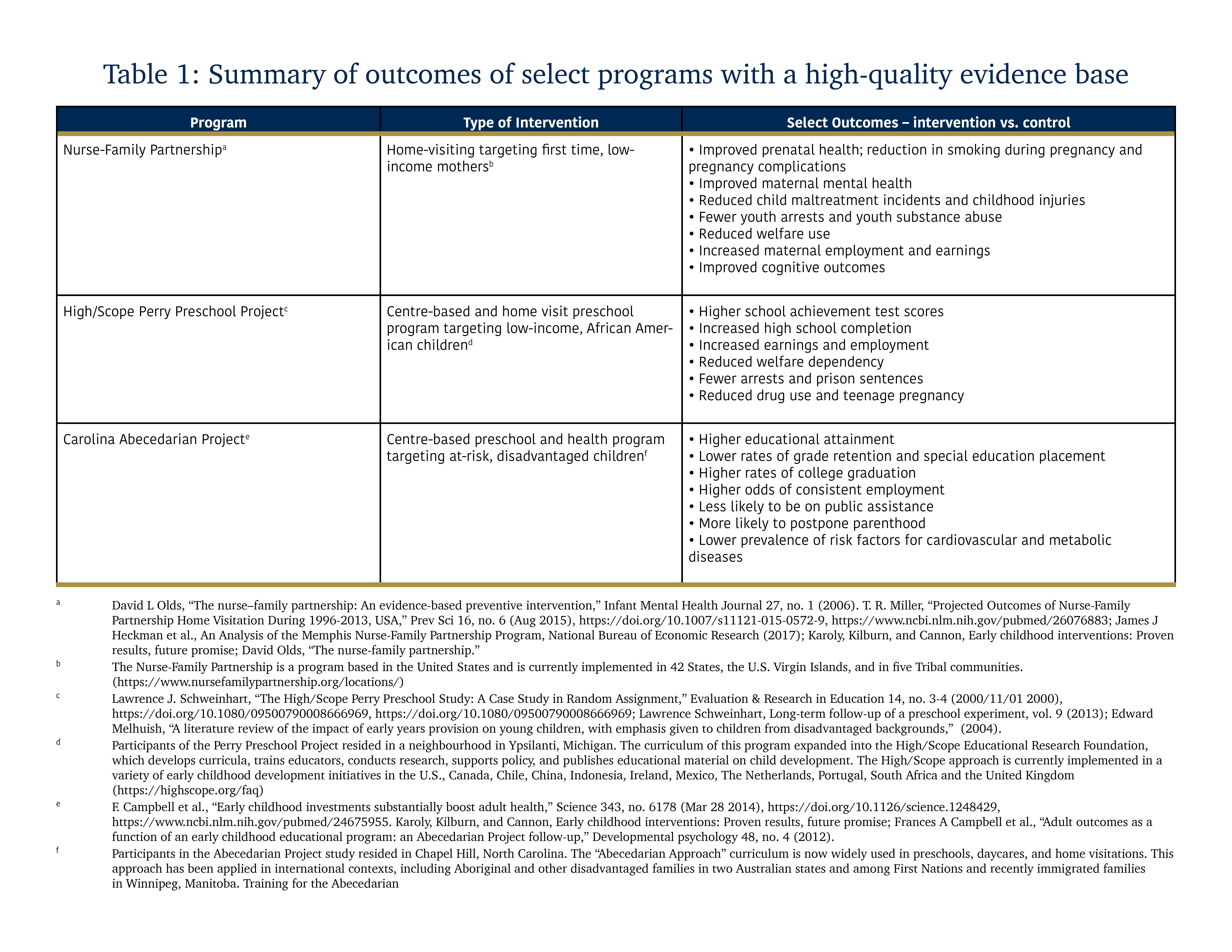

There are several examples of early childhood intervention programs that are supported by rigorous evaluation data (see Table 3). The Perry Preschool project, which began in 1962, is a notable example that has tracked participating children for over a 40-year period. Participation has been shown to improve outcomes across the board, from higher rates of college graduation to fewer arrests and prison sentences.[7] What is more, cost-benefit analyses show that for every USD1.00 spent, there is an estimated USD12.90 return.[8] There are few social programs with such a high return on investment. The lengthy follow-up period has also now allowed researchers to study intergenerational effects. A recent working paper by James Heckman, Nobel Prize Winner in economics for his work in ECD and the primary investigator of the Perry Preschool project, and his colleague Ganesh Karapakula,[9] found that children of original participants were less likely to be suspended from school, have higher levels of education and employment and lower levels of crime compared to the original control group’s children. They also found positive spillover effects for siblings of participants. The return on investment may therefore be even higher than previously thought.

The Indigenous population is the fastest growing in Canada, which increased by 42.5% between 2006 and 2016.[10] Failing to ensure that Indigenous children have the best possible start in life represents lost opportunities and costs. A 2018 report by the Public Health Agency of Canada found that the “prevalence of developmentally vulnerable kindergarten children is 2.0 times higher among Indigenous compared to non-Indigenous children”.[11] This is cause for concern, especially since these gaps tend to widen as opposed to shrink as the child progresses through school.[12] This increases the likelihood of lower educational attainment, which is linked to a host of poor outcomes into adulthood. The science is clear - investing in programs targeting healthy ECD has the potential to improve outcomes down the road and save money in the long run. Thus, it is interesting to explore: how has Canada leveraged this international evidence base to close gaps among Indigenous peoples?

The first federal programs targeting ECD among Indigenous peoples specifically began in the early 1990s.[13] Perhaps one of the most well-known federally funded early intervention programs is Aboriginal Head Start (AHS). First implemented in Indigenous off-reserve Indigenous communities (Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities – AHSUNC) in 1995, the program was extended to First Nations on-reserve (Aboriginal Head Start on Reserve – AHSOR) shortly after in 1998. For the most part, it is a centre-based preschool program targeting 3 to 5-year-olds, though the approach is flexible since individual communities design their own programs to best suit their needs. For example, communities may decide to also offer a home visiting component as part of their program. With a focus on spiritual, emotional, intellectual and physical growth, AHS employs a culture-centred approach to development and involvement of parents and guardians are a key aspect of the intervention. Overall, programs must support one or more of the following components: education, health promotion, culture and language, nutrition, social support and parental/family involvement.[14]

AHS is one among many ECD programs funded by the federal government that has been well-received by Indigenous communities.[15] The most recent national-level evaluation of the AHSUNC program reported notable improvements in school readiness and knowledge of Indigenous languages and culture among participating children; enhanced caregiving skills, social support and mental health among parents; and evidence that programs have been able to leverage other services in the community to meet the needs of children and families.[16]

When it comes to the AHSOR program, data is less comprehensive and considerably dated. One major challenge to understanding outcomes and efficiencies of the AHSOR program is the fact that it was evaluated within a cluster of federal programs targeting maternal and child health and ECD on-reserve.[17] Therefore, there is no way to know which outcomes can be directly attributed to the AHSOR program. Between 2008-2009 and 2012-2013, the Government of Canada spent $238.59 million on the AHSOR program, accounting for almost half of all expenditures for programs within this cluster.[18] What results did this investment produce, and how are they evaluating progress?

The answer to this question is further complicated by a lack of data collection for performance measurement. As the evaluation notes, “a main challenge in the collection and use of data identified by some national and regional office staff was in defining appropriate indicators and collecting measurable data for tracking progress in achieving outcomes,” stating the program would benefit from a review of the logic model. Baseline data is also largely unavailable, preventing the ability to monitor trends and progress. Analysis by Halseth and Greenwood find that participation in AHSOR appears to have many similar benefits for children and families as for those in the AHSUNC program, though this is based on the limited evidence that is available.[19] Overall, it is difficult to learn and make adjustments to enhance program effectiveness (and thus improve outcomes) if the right data collection tools or clearly defined outcomes are not in place.

This is part of a broader issue of understanding the impact of MCH and ECD programming. The current suite of federal programs has been difficult to assess at an aggregate level, as they are funded and implemented by several different departments. As a result, “Aboriginal childcare services differ in quantity, quality, and accessibility across provincial/territorial jurisdictions,”[20] making it difficult to consistently evaluate their impact. However, if the widespread disparities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in Canada that continue to persist are any indication, there is certainly room for improvement.

We can see from examples in the United States and in some cases in Canada, early intervention can and does work. Additional initiatives that employ a culture-centred approach like the AHS program have emerged in recent years. In Canada, a promising pilot project that has emerged in the last year is the Martin Family Initiative’s (MFI) Early Years. In line with best practices in early intervention, the aim of this pilot project is to improve outcomes for pregnant Indigenous women and their children living on a First Nations reserve through the development of a community-based initiative that centralizes Indigenous knowledge and cultural values in the context of child wellbeing.

Though it is in its early stages, preliminary evaluation findings indicate that phase one of program has been well-received by the community. Early years visitors report that they have been able to build trust with new mothers, which has opened the door for effective implementation and program acceptance. Participants appear to be enthusiastic about gaining new knowledge about pre- and postnatal health and development, which seems to translate into behaviour change that fosters healthy ECD. Home visitation and enhanced parental knowledge has also had run-off benefits for older siblings. Furthermore, sharing circles have allowed for deeper social connections and participation in culture-promoting activities. Early years visitors have also been able to connect families with resources and services in the community. Ongoing process evaluation will ensure its responsiveness to the community’s needs by program leaders.

In the context of the United States, The Family Spirit Program from Johns Hopkins University appears to be a success. It is a home-visiting intervention for American-Indian teenage mothers living in reservation communities, “designed to promote family-based protective factors and reduce behavioural health disparities among American Indian teen parents and their children”.[21] A culture-centred approach is employed to educate parents on healthy development and lifestyle for themselves and their children. The contents of the program include a focus on the reduction of behaviours such as harsh parenting and abuse that are associated with behavioural problems in children, as well as maternal mental health and behaviour that are incongruent with positive parenting.[22] Recruitment for this program took place between 2006 and 2008, and thus has been able to publish data on its outcomes.

In a 3-year follow-up study of the Family Spirit program,[23] researchers found that mothers in the intervention group exhibited significantly greater parenting knowledge, which had the largest effect size among all outcomes. They also reported a greater parental locus of control, which included factors such as parental efficacy and both parent and child control, as well as fewer depressive symptoms. In the domain of maternal emotional and behavioural outcomes, the greatest effect sizes were observed in outcomes related to substance abuse, with lower past month of marijuana use and illegal drug use. Additionally, mothers displayed fewer externalizing problems, which included issues such as opposition, defiance, rule breaking and social problems. Among children, improved outcomes were observed in externalizing (such as impulsivity, defiance, and aggression), and internalizing behaviours (such as anxiety, distress, and withdrawal).

(Please click to enlarge.)

By design, MFI’s Early Years program and the Family Spirit program fill some of the gaps existing federal programs fail to address. One fundamental difference is a rigorous, experimental approach to evaluation, which has not been thoroughly undertaken. Ongoing data collection provides a unique opportunity to establish Canada’s first longitudinal dataset tracking early intervention outcomes in the Indigenous context – an initiative which is long overdue – allowing for continuous program improvement. Given how influential a child’s environment is in healthy ECD, the MFI’s Early Years program’s impact will be evaluated using an approach that reflects outcomes across health, education and social services domains. It also leverages existing community programs implemented by the federal government, which can serve as an opportunity to maximize existing resources.

In terms of spending, the government has put their money where their mouth is. However, these issues run far deeper than just ticking a financial box. Now comes the more difficult but essential part of aligning these investments – taxpayer dollars – to producing tangible results. If outcomes do improve in the years to come, it will certainly be difficult to attribute it to any one initiative. Early intervention may not be a panacea, but it does have the potential to be part of a broader strategy to achieve substantive equality among Indigenous children. Before the next federal election, increasing funding programs like MFI’s Early Years is a sensible step in following through on promises made.

[1] "Budget 2019 Highlights: Indigenous and Northern investments," 2019, https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1553716166204/1553716201560.

[2] Government of Canada, "Budget 2019 Highlights: Indigenous and Northern investments."

[3] See IFSD brief on prevention.

[4] James J Heckman, "The case for investing in disadvantaged young children," CESifo DICE Report 6, no. 2 (2008); James J Heckman, "Skill formation and the economics of investing in disadvantaged children," Science 312, no. 5782 (2006); World Health Organization, Early child development: a powerful equalizer (2007), http://www.who.int/social_determinants/resources/ecd_kn_report_07_2007.pdf.

[5] World Health Organization, Early child development: a powerful equalizer; Deborah A Phillips and Jack P Shonkoff, From neurons to neighborhoods: The science of early childhood development (National Academies Press, 2000); Lynn A Karoly, M Rebecca Kilburn, and Jill S Cannon, Early childhood interventions: Proven results, future promise (Rand Corporation, 2005); Neal Halfon and Miles Hochstein, "Life Course Health Development: An Integrated Framework for Developing Health, Policy, and Research," The Milbank Quarterly 80, no. 3 (2002), https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.00019, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2690118/; James J Heckman, "The economics of inequality: The value of early childhood education," American Educator 35, no. 1 (2011); Eric I. Knudsen et al., "Economic, neurobiological, and behavioral perspectives on building America’s future workforce," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103, no. 27 (06/26 02/02/received 2006), https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0600888103, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1502427/; C. Hertzman and T. Boyce, "How experience gets under the skin to create gradients in developmental health," Annu Rev Public Health 31 (2010), https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103538; J Fraser Mustard, "Early brain development and human development," Encyclopedia on early childhood development (2010).

[6] Lynn A Karoly, M Rebecca Kilburn, and Jill S Cannon, Early Childhood Interventions: Proven Results, Future Promise (Rand Corporation, 2005)

[7] Campbell et al., "Adult outcomes as a function of an early childhood educational program: an Abecedarian Project follow-up."; Schweinhart, Long-term follow-up of a preschool experiment, 9.

[8] "Perry Preschool Project (Return on Investment)," 2019, accessed Apr 30, 2019, https://highscope.org/perry-preschool-project/.

[9] James J Heckman and Ganesh Karapakula, Intergenerational and Intragenerational Externalities of the Perry Preschool Project (2019).

[10] "Aboriginal peoples in Canada: Key results from the 2016 Census," (Internet), 2017, accessed 2018 Jul 25, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/171025/dq171025a-eng.htm.

[11] Public Health Agency of Canada, Key Health Inequalities in Canada: A National Portrait [Internet] (2018), https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/publications/science-research/key-health-inequalities-canada-national-portrait-executive-summary/hir-full-report-eng.pdf.

[12] J. J. Heckman, "Schools, Skills, and Synapses," Econ Inq 46, no. 3 (Jun 2008), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20119503; Patrice L. Engle and Maureen M. Black, "The Effect of Poverty on Child Development and Educational Outcomes," Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1136, no. 1 (2008), https://doi.org/doi:10.1196/annals.1425.023, https://nyaspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1196/annals.1425.023.

[13] Regine Halseth and Margo Greenwood, Indigenous early childhood development in Canada: Current state of knowledge and future directions, National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health (Prince George, BC, 2019), https://www.nccah-ccnsa.ca/docs/health/RPT-ECD-PHAC-Greenwood-Halseth-EN.pdf.

[14] Government of Canada, Evaluation of the Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities Program 2011-2012 to 2015-2016, (2017).

[15] Halseth and Greenwood, Indigenous early childhood development in Canada: Current state of knowledge and future directions.

[16] Halseth and Greenwood, Indigenous early childhood development in Canada: Current state of knowledge and future directions.

[17] In the evaluation, the AHSOR program is situated within a Healthy Child Development (HCD) cluster. Other programs in this cluster include: Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder, Canada Prenatal Nutrition Program – First Nations and Inuit Component, Maternal and Child Health, and the Children’s Oral Health Initiative.

[18] Government of Canada, Evaluation of the Healthy Living (2010-2011 to 2012-2013) and Healthy Child Development Clusters (2008-2009 to 2012-2013), (2014).

[19] Halseth and Greenwood, Indigenous early childhood development in Canada: Current state of knowledge and future directions.

[20] Jane P Preston, "Enhancing Aboriginal child wellness: The potential of early learning programs," First Nations Perspectives: The Journal of Manitoba First Nations 1, no. 1 (2008).

[21] Britta Mullany et al., "The Family Spirit Trial for American Indian teen mothers and their children: CBPR rationale, design, methods and baseline characteristics," Prevention Science 13, no. 5 (2012).

[22] Allison Barlow et al., "Paraprofessional-delivered home-visiting intervention for American Indian teen mothers and children: 3-year outcomes from a randomized controlled trial," American Journal of Psychiatry 172, no. 2 (2015).

[23] Barlow et al., "Paraprofessional-delivered home-visiting intervention for American Indian teen mothers and children: 3-year outcomes from a randomized controlled trial."