by Emily Woolner

Performance Evaluation of Gender Budgeting in Canada

Following the Liberal victory in the 2015 federal election, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau sent a strong message by establishing Canada’s first gender-equal cabinet. Since then, the federal government has been very vocal in its commitment to “embed feminism in all aspects of government work”.

It is no secret at the Liberal victory in 2015 was strongly affected by the support of female voters. According to Elections Canada, over 9 million women voted in the 2015 federal election, and women demonstrated a higher electoral participation rate (at 68.0%) than men (at 64.1%), in all age groups. Certainly, the government’s expansion of GBA+ is a practical pitch to crucial Liberal voters. Likewise, many of the government’s primary commitments outlined in the Mandate Letter Tracker exhibit a focus on gender equality.

A notable example is the implementation of ‘gender-based analysis plus’ (GBA+), an analytical tool designed to assess government policies, programs, and legislation through the lens of diversity. GBA+ is the process by which government initiatives are reviewed for their impact on different populations based on a number of identity factors. Although it has been used at the federal level since the mid-1990s, the government has expanded the scope and effect of this program in recent years. Since 2015, Status of Women Canada (SWC), the Treasury Board Secretariat, and the Privy Council Office have shared responsibility for integrating GBA+ into government processes, making it a mandatory component for all Treasury Board submissions, memoranda to Cabinet, and departmental results frameworks. Since 2018, GBA+ has become the guiding framework for gender budgeting in Canada.

While gender budgeting is a stated policy goal of the current government, what does it mean in practice? How do Canada’s practices on GBA+ compare to those in other countries? Does the GBA+ generate outcomes?

The IMF’s 2017 survey on gender budgeting among G7 countries is clear that statements on gender budgeting impact assessments do not imply outcomes. It’s “not whether an initiative is labeled as ‘gender budgeting’ but whether fiscal policies and PFM practices and tools are formulated and implemented with a view to promoting and achieving gender equality objectives, and allocating adequate resources for achieving them” according to the IMF.

In the survey Canada is recognized as having implemented gender budget statements and gender impact assessments into its budgetary process, as well as having partially applied relevant gender performance indicators, parliamentary control and oversight measures, and gender audits. But what does this really mean? How is Canada faring?

The challenge, it appears, is the translation of stated commitments into practice. According to the Auditor General’s (AG) 2015 report, improvements are needed to implement and monitor the effectiveness of GBA+. In response, the government has developed an Action Plan on Gender-based Analysis (2016-2020) to bolster this tool as a rigorous practice across departments and agencies.

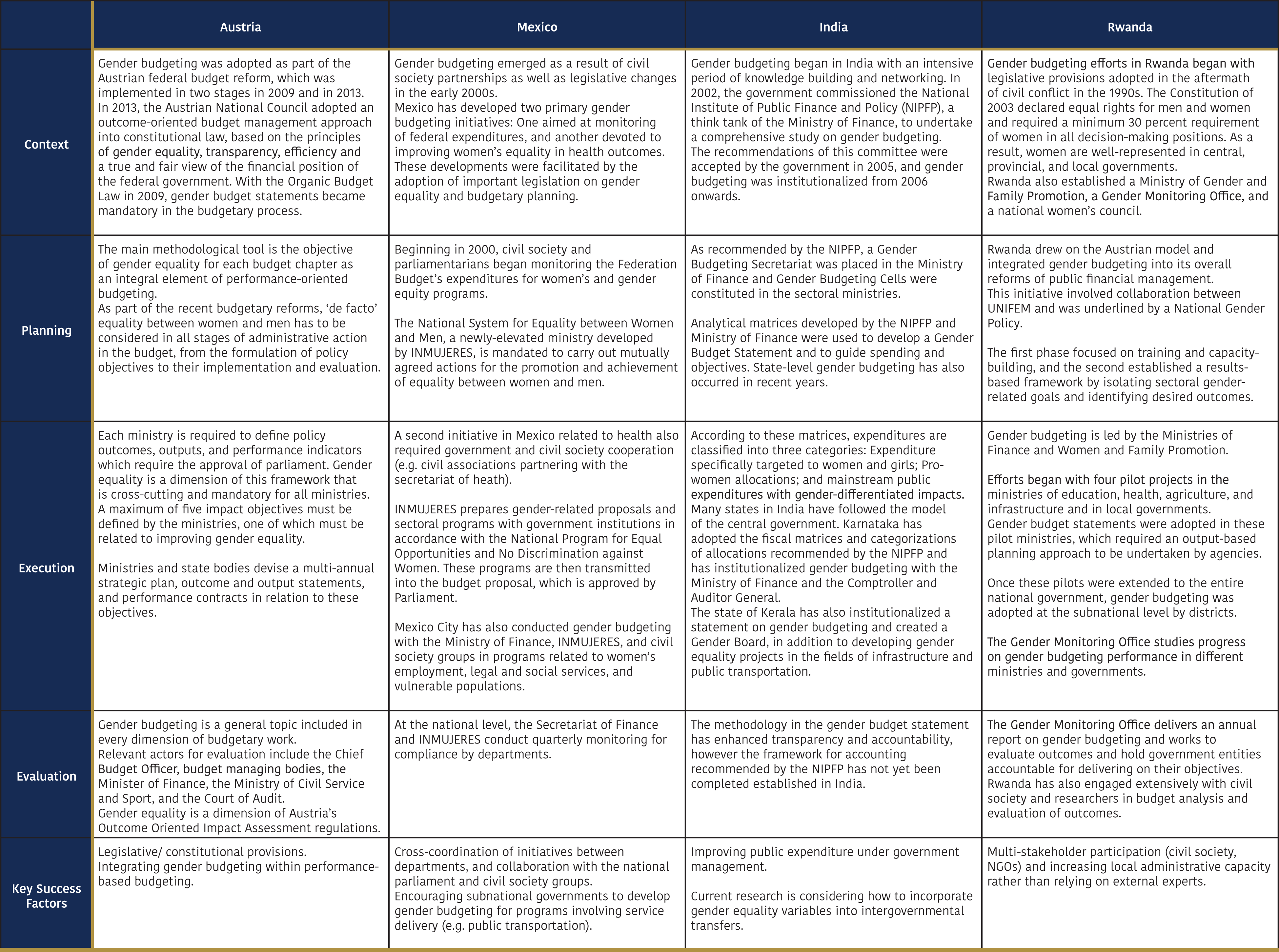

International peers outside of the G7 have lessons for Canada to help it enhance the application of GBA+ as more than a policy statement, but an integral component of its budget plans and performance assessments.

Consider Austria, an early adopter of gender budgeting, and one of the best performing countries in this area. As part of its recent budgetary reforms, Austria has adopted an outcome-oriented approach to gender budgeting. This means that all federal ministries and national bodies are required to submit gender equality objectives and devise appropriate outputs and indicators in preparation for the annual budget. Austria also incorporates gender equality evaluations into impact assessments, performance reports, and into the purview of the Austrian Court of Audit. By connecting spending to measurable and relevant outcomes, the OECD has called the Austrian approach a “leading international practice” in gender budgeting. Canada could emulate this practice by integrating gender budgeting into a performance management framework. To do this, the federal government could develop and align equality targets to resource-allocation decisions for priorities in the Gender Results Framework. This could enhance political and administrative transparency for resources and for results.

Of course, progress can also be made at the local level. India and Mexico, for example, have extended efforts to subnational jurisdictions. In India, the government has developed gender budget statements using analytical matrices for gender budgeting, which ministries and departments use to design policies and request funding. This is arguably a more effective approach than the gender budget statement used in Canada, which is more akin to a mission statement. India has also institutionalized a Gender Budget Secretariat into its Ministry of Finance and has created Gender Budgeting Cells (GBC) in different sectoral ministries. These GBCs are governed by a charter established by the Ministry of Finance and are responsible for reviewing departmental programs and conducting performance audits, organizing training and workshops, and disseminating information and best practices. The states of Karnataka and Kerala have integrated similar measures into their respective state machineries.

Mexico has made important strides as well. In addition to increasing funding for women—particularly in the health sector—and improving monitoring and implementation mechanisms at the national level, Mexico City has also launched measures relating to employment, social services, and safe urban transportation for women. Indeed, it is sometimes more practical to focus on specific policy sectors in order to achieve meaningful gender-equality results, as evidenced by the case of Rwanda. Rwanda began gender budgeting with four pilot programs in the ministries of education, health, agriculture, and infrastructure, before expanding its practices to national and subnational governments. So too in Canada, an active strategy on a smaller number of critical policies, well-executed with provincial/territorial and municipal partners, could be more impactful than a passive response across the federal government.

The introduction of gender budgeting is a relatively new spending analysis tool, and greater evidence of its impact may appear in the future. However, progress in Canada will depend in part on a more complete implementation of the GBA+ tool with a greater role for public servants, and perhaps an even bigger commitment by our political leaders towards the allocation of resources and equality targets. In the meantime, Canada is making positive steps but remains well behind global leaders like Austria. Based on such cases, the crucial lesson for the federal government is to implement gender budgeting to the extent that we can measure concrete progress, rather than track promises.

(Please click to enlarge.)