Thunderbird Partnership Foundation (Thunderbird) is a national non-profit organization that advocates for collaborative, integrated and wholistic approaches to healing and wellness for First Nations culturally based substance use and mental wellness services. Thunderbird is a division of the National Native Addictions Partnership Foundation Inc. (NNAPF Inc., established in 2000), and rebranded as Thunderbird Partnership Foundation in 2015. Thunderbird advocates for 42 adult addictions treatment programs known as the National Native Alcohol and Drug Abuse Program (NNADAP) and the First Nations community-based prevention programs, and 10 youth First Nations addictions treatment centres known as the National Youth Substance Abuse Program (NYSAP), by supporting operating and delivery activities, such as development of resources, coordination, training, data gathering, and analysis.

Thunderbird led development of the Native Wellness Assessment (NWA™) that demonstrates the effect of cultural interventions as treatment. Using a continuum of care perspective that emphasizes wellness of the whole person through a strengths-based approach, Thunderbird has worked to align accreditation, practice, and evaluation.

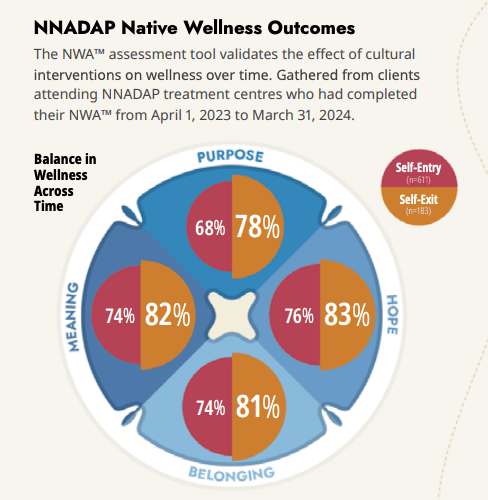

Thunderbird strives to support culture-based outcomes of Hope, Belonging, Meaning, and Purpose for First Nations individuals, families, and communities.

Background (First Nations addictions treatment)

There is a long history of addictions treatment facilities and First Nations community based prevention programming. The National Native Alcohol and Drug Abuse Program (NNADAP) established 49 treatment centres in 1975-76. Governed by surrounding First Nations, the centres were supported by leadership, communities, and the federal government. Federal funding for the centres stabilized in 1982, and advocacy efforts turned to the continuum of care.

First Nations also began building associated prevention services in community, with expectations that First Nations would provide “continuing care” services for those who have completed the residential treatment program. However, because federal funding is based on a formula that accounts only for population size and remoteness, the funding First Nations communities receive does not match the need for community-based substance use and addiction programming, resources, and care pathways. This meant that small populations could not build much with their allocation and resources were often absorbed into existing activities. Through this funding formula, operating budgets do not adequately reflect salaries common in the field and so over time, there are challenges to workforce recruitment and retention.

Activities in five newly funded First Nation youth treatment centres in 1995 would be a first step in redirecting the trajectory of treatment centres for First Nations Youth. The funding criteria documented as terms and conditions of the contribution agreements between youth treatment programs, NYSAP, and the First Nations Inuit Health Branch required youth treatment centres seek and maintain health services accreditation from within their existing budgets. The requirement drove two principal changes: 1) First Nations Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB) agreed to support the adult treatment facilities and NNADAP who chose to pursue accreditation would qualify for a budget increase (as there’s a cost for accreditation and for addressing any identified gaps); however there was no additional funding provided to NYSAP or NNADAP treatment centers to address identified risks or other gaps; 2) Accreditation Canada agreed to work with First Nations to review standards, train First Nations staff accreditation surveyors, and include First Nations on their board. These were significant steps, laying the foundation for future evidence-based approaches focused on culture.

The five youth treatment centres adopted a standard approach to data gathering on common indicators, e.g., school completion/attendance, incarceration, suicide ideation, etc. They unanimously agreed that culture would be the focus of their therapeutic models. The lessons from the youth treatment centres were profound. Accreditation (nationally recognized), occupancy (beds), and operations (intake) could be addressed successfully through an Indigenous lens. The example set a course forward.

A 1998 review of NNADAP resulted in 37 recommendations, including the establishment of NNAPF to focus on a continuum of care in addictions treatment. Expectations and hopes for NNAPF were high among First Nations. Funding, however, was inconsistent, and with restricted resources, a small team of five staff was taking on unrelated projects to remain operational. Their decisions created space to eventually evaluate the impacts of a culturally informed approach to addictions treatment.

Practice and program framework (NNADAP/ NYSAP)

NNAPF / Thunderbird began to gain capacity to fulfill its mandate to act on the 37 recommendations of the 1998 NNADAP review. Indigenous knowledge and a culture-based approach guides Thunderbird in the development of resources and tools to support First Nations service providers in the application of Indigenous Knowledge and culture-based practices that address the root causes of substance misuse, e.g., impacts of colonization, such as poverty, lack of access to land and natural resources, lack of housing, family violence, deprivation, etc.

Through a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) funded research project, Thunderbird and partners identified approximately 52 culture-based practices that are common across First Nations cultures to address substance use and addictions. These include: sharing circles, sweat lodge ceremony, the use of culture based medicines such as those used for smudge, traditional foods, and the importance of identity. Cognitive behavioural therapy, psychotherapy, motivational interviewing, and land-based healing are all used without naming them as such. The results of the approach, while positive, were not being quantified in Western-based terms. That would eventually change.

In 2007, NNAPF became co-chair of the National Advisory Committee that would facilitate a national review of the NNADAP and NYSAP programs (originally, meant to be co-chaired only by the Assembly of First Nations and Health Canada). The Committee was informed that the goal of the review of NNADAP and NYSAP was to ensure the national program operated with a clear evidence base. The existing evidence base for addictions treatment is based largely on white adult males, with no inclusion of Indigenous populations or knowledge. The question became, “whose evidence are we using?,” to undertake the review. Ultimately, the approach adopted by the committee would translate between the Indigenous and non-Indigenous worldviews.

With the review of the national addictions treatment and prevention program underway, regional conversations made clear that First Nations wanted research into how and why culture makes a difference in treatment. With the grant from the CIHR, NNAPF worked through a willing coalition of treatment centres in their network (following their individual ethics protocols), researchers, and other partners to explore the matter.

There were two tracks to the project:

- An Elder undertook a national environmental scan of Indigenous knowledge to understand what makes a person whole and healthy (balance of mind, body, spirit, and emotion); cultural practices to facilitate a whole and healthy person; and the expected results from the foundation of Indigenous Knowledge;

- Western-based scientists undertook discursive analysis of the Indigenous knowledge team’s findings to ensure the psychometrics of the assessment were accurately measuring Hope, Belonging, Meaning, and Purpose as facilitated through culture and not other important aspects of the addictions treatment programs. The result was the Native Wellness Assessment (NWA™) released in 2015.

The challenge of wage parity

Since 1998, there have been expressed concerns about wage parity of treatment centre employees.

In some communities, expressing the parameters for parity can be challenging because they may not use Western language to describe what they’re doing and how they’re doing it. For instance, an Elder may spend time working with clients during the day and with the spirits at night. Those contributions to the physical and spiritual worlds are essential to capturing wage parity. To this end, Indigenous knowledge must be defined as a factor in treatment centre jobs from front-line to back office.

Staff retention is a challenge. Centres train staff and invest in their development. Then, they leave for better paying and less stressful jobs. That’s problematic for service delivery and continuity.

Assessing wage parity requires comparison of common functions and roles, as well as the presenting client characteristics. Often, treatment centre employees deliver more than their defined roles. This means that comparing wages to similar positions should be adjusted for additional functions, knowledge, and geographic realities of First Nations.

Data collection and analysis

The NWA™ is an expression of the integration of Indigenous and Western world views, rooted firmly in Spirit and wellness through balance of spirit, emotion, mind, and body. The NWA™ is now used in both youth and adult treatment centres and in many community-based services and across service sectors, including Corrections, Child and Family Services, Tribal Wellness Courts, and non-indigenous community mental health services that include culture-based interventions. The tool is used to inform service delivery, inform a model for case management, program planning, and funding and reporting, which allows for analysis associated to culture, land, and well-being. Evidence generated with data gathered through the NWA™ can demonstrate service quality and workforce competency specific to First Nations culture.

The NWA™ consists of four wellness outcomes: Hope, Belonging, Meaning, and Purpose. As described on the Thunderbird Partnership Foundation website, it contains 66 independent statements and 52 cultural intervention practices, which are categorized into the 13 wellness descriptors, across the four wellness outcomes.[1]

The NWA™ features two key assessment types. One is a Self-reporting Form filled out by the client to establish their baseline cultural connections and experiences at program entry, followed by a comparison of wellness. The second is the Observer Rating Form, completed by a counselor or elder familiar with the clients’ treatment progress.[2] Assessments are intended to be conducted two to three times for each client, dependent on program duration and ongoing contact post treatment.

The NWA™ is accessible through the Addictions Management Information System (AMIS), treatment centres, or directly on Thunderbird’s website.[3] If an organization is not using AMIS, it can enter into a data-sharing agreement with Thunderbird, who will produce individual and aggregate reports. Thunderbird will collect the data through a web-based platform, input de-identified data into a designated NWA™ pathway in AMIS, analyze the data with the support of epidemiologists, and generate a report. Thunderbird is also exploring options for developing an NWA™-specific platform.

AMIS

AMIS, developed in 2014, is a national data and case management system for NNADAP/NYSAP treatment centres. It is a free, voluntary option available for treatment centres and First Nations communities or organizations.[4] It is being used in community-based addiction programs that offer day programs, outpatient programs, land-based programming, etc. Training to use AMIS is available through Thunderbird and eCentre Research, which provides training modules and technical support.[5]

AMIS can store competencies and client records, facilitate referrals and information sharing across centres, assist with patient screening, support goal setting, monitor treatment effectiveness, and track clients’ aftercare.[6] It has integrated both the NWA™ and the Drug Use Screening Inventory-Revised (DUSI-R), which is a trauma scale that treatment workers can use to assess First Nations clients.[7]

Treatment centres and First Nations own their data in accordance with OCAP® Principles. Client-level data is not accessible to Thunderbird unless permission is granted by the treatment centre. Data sharing agreements, which are signed between Thunderbird and treatment centres/First Nations prior to implementation of AMIS, allow Thunderbird to hold regionally and nationally aggregated (deidentified) data. Centres are able to generate standardized individual client and annual reports using their aggregated data. Treatment centres are not required to report back to Thunderbird. As outlined in their data sharing agreement, Thunderbird can produce aggregate reports. Users of AMIS are also supported in data cleaning to ensure that their data is accurate. Webinars and annual in-person workshops facilitate & maintain capacity of the service providers to maintain their own data and identify what information can be extracted from AMIS to produce knowledge to inform program changes, design and deliver.

As of 2025, AMIS has been implemented in 34 NNADAP treatment centres, 10 NYSAP treatment centres, and 18 First Nation community organizations.[8] Further, as of 2023, there are an additional 50 First Nations pilot testing the system. It should be noted that 39 of the 44 treatment centers using AMIS are accredited with standards of excellence by 1 of 3 Canadian Accreditation organizatios.[9] Thunderbird’s research team actively engages with treatment centres and First Nations in using AMIS and the NWA™.

Working alongside centres

Thunderbird undertakes outreach efforts to share its tools, including through tradeshow booths, conference presentations, regional discussions and engagement, and at data-supported speaking engagements. Additionally, it has a dedicated human resources team to support those using or interested in using AMIS and/or the NWA™. It provides continuous training and education to existing and new users. This is especially important to ensure that new treatment centre employees receive the necessary training to effectively collect, input, and analyze data.

Results of assessments from 2023-2024 indicate an improvement in self-reported Hope, Belonging, Meaning, and Purpose upon exiting the treatment program (Figure 1). Success according to the NWA™ should be considered at the individual and centre levels. The data can help inform how cultural interventions support wellness, identify areas where interventions need improvement, highlight how individuals could be further supported, guide program and organizational planning, and establish a baseline for individuals, etc. The data from AMIS and other surveys, e.g., First Nations Opioid and Methamphetamine Survey, inform Thunderbird’s strategic priorities, advocacy efforts, and policies.

Lessons learned

Thunderbird has developed an integrated model that aligns accountability and funding through operations and data gathering with culture at the centre of the approach. Spirit-centred, First Nations culture-based approaches benefits from a two-eyed seeing approach as it guides the work and demonstrates its results. This requires understanding people and their changes in-context, i.e., capturing their starting point and assessing change. The approach supports local understanding and data gathering with sufficient alignment for aggregation and national (across treatment centres) reporting.

Thunderbird has built trust with treatment centres and First Nations communities as a centre of excellence that supports data gathering and analysis. The development of Thunderbird’s data gathering tools (e.g., AMIS, NWA™, etc.) was led and informed by treatment centres and relevant partners. Working groups actively inform the continuous improvement of these tools. Listening to and involving stakeholders, using a collaborative approach to develop resources and tools, and having a dedicated team for data management have been essential to Thunderbird’s growth as a centre of excellence.

Thunderbird models and supports an integrated and wholistic approach to service delivery. Serving as a hub for training, data analysis, and advocacy, the associated treatment centres pursue locally relevant cultural practices. With standardized accreditation and reporting, the adult and youth treatment centers regularly measure and monitor the impact they are having on people. The model offers lessons and pathways for other forms of service delivery in First Nations where distinct accreditation and data gathering is required and can be applied for advocacy.

[1] Thunderbird Partnership Foundation, “The Indigenous Wellness Framework: Understanding Hope, Belonging, Meaning & Purpose,” accessed on March 6, 2025, https://thunderbirdpf.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/NWA-Poster_EN-Web.pdf.

[2] Thunderbird Partnership Foundation, “The Indigenous Wellness Framework: Understanding Hope, Belonging, Meaning & Purpose,” accessed on March 6, 2025, https://thunderbirdpf.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/NWA-Poster_EN-Web.pdf.

[3] Thunderbird Partnership Foundation, “Addictions Management Information System,” accessed on March 7, 2025, https://thunderbirdpf.org/addictions-management-information-system/.

[4] Thunderbird Partnership Foundation, “Addictions Management Information System,” accessed on March 7, 2025, https://thunderbirdpf.org/addictions-management-information-system/.

[5] Thunderbird Partnership Foundation, “Addictions Management Information System,” accessed on March 7, 2025, https://thunderbirdpf.org/addictions-management-information-system/.

[6] Thunderbird Partnership Foundation, National Treatment Gathering: Final Report (Thunderbird Partnership Foundation, February 2024): 54, https://thunderbirdpf.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/National-Treatment-Gathering_Final-Report_EN-WEB.pdf.

[7] Thunderbird Partnership Foundation, “Addictions Management Information System,” accessed on March 7, 2025, https://thunderbirdpf.org/addictions-management-information-system/.

[8] Thunderbird Partnership Foundation, “The Indigenous Wellness Framework: Understanding Hope, Belonging, Meaning & Purpose,” accessed on March 6, 2025, https://thunderbirdpf.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/NWA-Poster_EN-Web.pdf.

[9] Thunderbird Partnership Foundation, First Nations Substance Use Summit (Thunderbird Partnership Foundation, August 4, 2023): 25, https://thunderbirdpf.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Substance-Use-Summit-Report_EN-WEB.pdf.